Galatia Channel:Underclay of Springfield Coal

Underclay of Springfield Coal

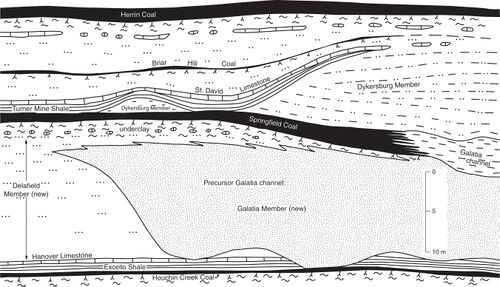

Like most coal beds in the Illinois Basin, the Springfield normally is underlain by nonfissile mudstone that miners call underclay. Features such as roots, slickensides, microscopic structures, and secondary carbonate nodules demonstrate that the underclay is a paleosol, the product of overprinting by soil development in previously deposited sediment. A paleosol is not a lithostratigraphic unit. From the stratigraphic point of view, the Springfield underclay is considered part of the Delafield Member except close to the Galatia channel, where the underclay is part of the Galatia Member.

Where the underclay is part of the Delafield Member, it is generally 4.9 to 9.8 ft (1.5 to 3 m) thick and in places reaches 13.1 ft (4 m). Black, organic-rich claystone commonly occurs at the top. The remainder is olive-gray to greenish-gray claystone that grades downward to siltstone or silty mudstone (Figure 9). All except the uppermost 1.0 to 2.0 ft (0.3 to 0.6 m) is generally calcareous and contains irregular nodules of limestone or dolomite. A solid layer of carbonate rock as thick as 3.3 ft (1 m) occurs in places. This is microgranular, argillaceous to silty, and lacks fossils other than root traces. The lower part of the paleosol is commonly riddled with irregular vertical fractures lined with siderite, calcite, and dolomite. These soils have characteristics of Calcisols and Vertisols.

Where underclay belongs to the Galatia Member, it is rarely thicker than 3.3 ft (1 m) thick and less strongly developed than in the Delafield Member. Root traces, slickensides, and granules or nodules of siderite are present, but carbonate nodules are rare and the rock is not calcareous. In places close to the Galatia channel, no paleosol is present, and the Springfield Coal grades downward to laminated, carbonaceous shale. Such soils have characteristics of Protosols.

The Springfield underclay exhibits a complex climatic history. Detailed examination (Rosenau et al. 2013)[1] indicates that the soil formed mostly under a seasonally dry climatic regime, leading to vertic features. Late in its history, the soil underwent pronounced gleying, suggesting a change toward a much wetter climate. In places, the top of the paleosol grades into the base of the coal through a transitional zone of organic-rich shale, suggesting the development of clastic swamps prior to the onset of peat formation.

Because the area away from the channel was topographically higher and better drained, soils developed during the entire interval of time while the Galatia precursor channel was being eroded and back-filled. Calcite nodules and caliche layers require a subhumid to semiarid climate, strongly seasonal with distinct wet and dry seasons (Cecil and Dulong 2003)[2]. In contrast, soil formation within the Galatia meander belt was frequently interrupted by lateral channel shifts. This low-lying, poorly drained, and frequently disturbed area did not permit long-term pedogenesis or caliche development. The youngest landscape, along the riverbanks, saw little or no soil development.

Primary Source

References

- ↑ Rosenau, N.A., N.J. Tabor, S.D. Elrick, and W.J. Nelson, 2013, Polygenetic history of paleosols in Middle–Upper Pennsylvanian cyclothems of the Illinois basin, U.S.A.: Journal of Sedimentary Research, v. 83, p. 606–668.

- ↑ Cecil, C.B., and F.T. Dulong, 2003, Precipitation models for sediment supply in warm climates, in C.B. Cecil and N.T. Edgar, eds., Climate controls on stratigraphy: SEPM (Society for Sedimentary Geology), Special Publication 77, p. 21–27.