Galatia Channel:St. David Limestone Member

St. David Limestone Member

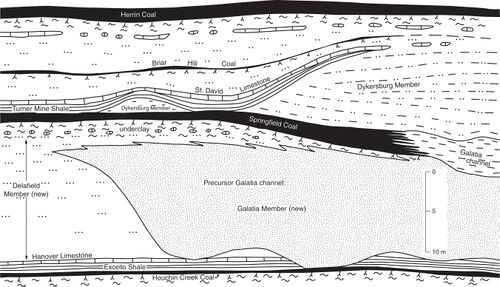

The St. David is marine limestone that overlies the Turner Mine Shale (Figure 4). Savage (1927)[1] named the unit, whereas Wanless (1956)[2] designated (but did not describe) a type section in Fulton County, western Illinois. The name “Alum Cave Limestone” has been used for the same unit in Indiana. Wanless (1939)[3] was the first to use Alum Cave in its present sense. The name St. David therefore has priority and is used in this report.

The St. David is medium to dark gray, argillaceous, lime mudstone to wackestone containing an abundant normal-marine fauna of brachiopods, bivalves, gastropods, cephalopods, ostracods, crinoids, fusulinids, and bryozoans (Savage 1921[4]; Wanless 1957[5]; Shaver et al. 1986[6]).

The member is practically coextensive with the Springfield Coal. In the Fairfield Basin and parts of western Kentucky, the limestone is less than 1 ft (30 cm) thick and consists of dark gray, argillaceous, fossiliferous lime mudstone to wackestone. On the Eastern Shelf in Indiana, the limestone is as thick as 10 ft (3 m) but more commonly 1 to 4 ft (0.3 to 1.2 m), in two layers separated by thin shale (Wier 1961)[7]. In northwestern Illinois, the unit is normally a few inches (centimeters) to about 2 ft (60 cm) thick but locally exceeds 6.6 ft (2 m; Wanless 1957[5]). Thicker St. David, lighter colored and less argillaceous than that found in the basin, also occurs on areas of the Western Shelf where the Springfield Coal is thick enough to mine. Along with the Turner Mine Shale, the St. David pinches out where the Dykersburg Shale is thick (~32.8 ft [10 m] or more).

The limestone closely resembles the older Hanover Limestone and probably was deposited under similar conditions. Like the Hanover, the St. David appears to have developed better in the shallow waters at the margins of the Illinois Basin than in the deeper waters of the basin interior.

Canton Shale

Savage (1921)[4] named the Canton Shale for the city of Canton in Fulton County, western Illinois. Little has been published about this unit. As depicted by Willman et al. (1975)[8], the Canton Shale occupies the interval between the St. David Limestone and the Briar Hill Coal (Figure 4). The following information is based on a cursory inspection of selected core records and observations in mines.

Generally, the Canton is an upward-coarsening succession of shale, siltstone, and fine-grained sandstone. Shale in the lower part contains numerous bands and nodules of siderite. Brachiopods and other marine fossils are common near the base. Sandstone in the upper Canton tends to be shaly and thinly layered. A few well records indicate a sharp contact between upper sandstone and lower shale, but deep channel incision is unknown. At the top of the Canton is the weakly developed underclay of the Briar Hill Coal. The thickness of the member is normally 10 to 50 ft (3 to 15 m), but the Canton reaches 82 ft (25 m) thick in Webster County, Kentucky.

Two problems arise in defining the Canton Shale. One problem, which does not concern this study, arises where the Briar Hill Coal is absent and the Canton cannot be distinguished from the unnamed clastic rocks overlying the Briar Hill position. The other difficulty is separating the Canton from thick Dykersburg Shale where the Turner Mine and St. David Members are missing. Core records indicate that the Canton thins to less than 9.8 ft (<3 m) where the Dykersburg is thicker than about 49.2 ft (15 m).

In depositional terms, the Canton Shale is more or less a repetition of the Delafield Member. The unit reflects the shoreline prograding into a shoaling basin during highstand to early regression.

Briar Hill Coal

The youngest unit considered in this report, the Briar Hill Coal (Figure 4) is thin but widely persistent in southeastern Illinois, southwestern Indiana, and western Kentucky. Glenn (1912)[9] named the coal in Union County, Kentucky, whereas Butts (1925)[10] extended the Briar Hill into southeastern Illinois. The same coal in Indiana has been called the Bucktown Coal Member (Shaver et al. 1970)[11]. Because Briar Hill has priority, usage of Bucktown should be discontinued.

The Briar Hill is confined to the southeastern part of the Illinois Basin in approximately the same region as the southeastern area of thick Springfield Coal. It extends above the Galatia channel except where the Dykersburg Member approaches its greatest thickness. Generally, the Briar Hill is a single bench of bright-banded coal between 9.8 and 19.7 in. (25 and 50 cm) thick. The maximum known thickness is about 50 in. (130 cm) in Sullivan County, Indiana. Where the Briar Hill is thinner than 10 in. (25 cm), the coal commonly becomes shaly. The Briar Hill rests on a weakly developed paleosol, commonly little more than a thin, root-penetrated interval of laminated silty mudstone or siltstone. Above the coal is a shaly succession that typically coarsens upward. A thin layer of impure marine limestone or fossiliferous shale may occur at the base. No black phosphatic shale, comparable to the Excello or Turner Mine Shale, accompanies the Briar Hill Coal.

Additional Reading

St. David Limestone Member on ILSTRAT

Canton Shale Member on ILSTRAT

Briar Hill Coal Member on ILSTRAT

Primary Source

References

- ↑ Savage, T.E., 1927, Significant breaks and overlaps in the Pennsylvanian rocks of Illinois: American Journal of Science, v. 14, p. 307–316.

- ↑ Wanless, H.R., 1956, Classification of the Pennsylvanian rocks of Illinois as of 1956: Illinois State Geological Survey, Circular 217, 14 p.

- ↑ Wanless, H.R., 1939, Pennsylvanian correlations in the Eastern Interior and Appalachian coal fields: Geological Society of America, Special Paper 17, 130 p.

- ↑ a b Savage, T.E., 1921, Geology and mineral resources of the Avon and Canton Quadrangles: Illinois Geological Survey, Bulletin 38, p. 209–271.

- ↑ a b Wanless, H.R., 1957, Geology and mineral resources of the Beardstown, Glasford, Havana, and Vermont Quadrangles: Illinois State Geological Survey, Bulletin 82, 233 p., 7 pls.

- ↑ Shaver, R.H., C.H. Ault, A.M. Burger, D.D. Carr, J.B. Droste, D.L. Eggert, H.H. Gray, D. Harper, N.R. Hasenmueller, W.A. Hasenmueller, A.S. Horowitz, H.C. Hutchison, B. Keith, S.J. Keller, J.B. Patton, C.B. Rexroad, and C.E. Wier, 1986, Compendium of Paleozoic rock-unit stratigraphy in Indiana—A revision: Indiana Geological Survey, Bulletin 59, 203 p., 2 pls.

- ↑ Wier, C.E., 1961, Stratigraphy of the Carbondale and McLeansboro Groups in southwestern Indiana: Indiana Geological Survey, unpublished manuscript, 147 p., and unnumbered appendix. (available in Herman B. Wells Library, Indiana University, Bloomington).

- ↑ Willman, H.B., E. Atherton, T.C. Buschbach, C. Collinson, J.C. Frye, M.E. Hopkins, J.A. Lineback, and J.A. Simon, 1975, Handbook of Illinois stratigraphy: Illinois State Geological Survey, Bulletin 95, 261 p.

- ↑ Glenn, L.C., 1912, A geological reconnaissance of the Tradewater River region, with special reference to the coal beds: Kentucky Geological Survey, Bulletin 17, 75 p.

- ↑ Butts, C., 1925, Geology and mineral resources of the Equality–Shawneetown area: Illinois State Geological Survey, Bulletin 47, 76 p., 2 pls.

- ↑ Shaver, R.H., A.M. Burger, G.R. Gates, H.H. Gray, H.C. Hutchison, S.J. Keller, J.B. Patton, C.B. Rexroad, N.M. Smith, W.J. Wayne, and C.E. Wier, 1970, Compendium of rock-unit stratigraphy in Indiana: Indiana Geological Survey, Bulletin 43, 229 p.