Walshville Member

Lithostratigraphy: Carbondale Formation >>Walshville Member

Chronostratigraphy: Paleozoic Erathem >>Pennsylvanian Subsystem >>Desmoinesian Series

Allostratigraphy: Absaroka Sequence

Primary source

Nelson, W.J., P.H. Heckel and J.M. Obrad, 2022, Pennsylvanian Subsystem in Illinois: Illinois State Geological Survey, Bulletin (in press).

Contributing author(s)

W.J. Nelson

Name

Original description

In an unpublished dissertation, Johnson (1972) used the name “Walshville channel” for a major paleochannel that existed during formation of the Herrin Coal. Allgaier and Hopkins (1975) published the first description of the Walshville channel. In an unpublished master’s thesis, Ledvina (1988, p. 632) proposed the name “Walshville Sandstone Member” for “sandstone, conglomerate, and siltstone that fill the Walshville channel, channels secondary to it, and sheet phases over shales where the non-marine roof sequence [Energy Shale] overlies the [Herrin] Coal.” Ledvina’s proposal is adopted here, with modifications.

Derivation

The name of the channel and the member is derived from Walshville, an unincorporated village about 6 mi (10 km) east of Mount Olive in Montgomery County, Illinois. Johnson (1972) selected the name because Walshville lies close to the subsurface trace of the channel. Founded in 1840 as Mount Kingston, the town was renamed in 1854 after site owner Michael Walsh (Callary 2009).

Other names

None.

History/background

As defined here, the Walshville Member comprises clastic strata that fill the Walshville channel and other channels of similar age throughout the Illinois Basin. The Walshville Member is partly older than the Herrin Coal and partly the same age. The Walshville fills paleovalleys that are incised through the Big Creek Shale and cut as deeply as the Oak Grove Limestone. Although the Energy Shale Member is intimately associated with the Walshville channel, the Energy Shale is younger than the Herrin Coal and distinct from the Walshville Member. However, differentiating the Energy and Walshville Members is difficult where the Herrin Coal is absent.

Type section

Type location

No surface exposures of the Walshville Member are known to exist. Mining operations at the Burning Star No. 5 Mine in Jackson County revealed portions of the Walshville channel at its southern terminus. Descriptions of mine exposures have been published (Dutcher et al. 1977, 1983), but all pits have been backfilled and reclaimed. Although core descriptions that include part or all of the Walshville Member are available, no core suitable for a type section has been preserved.

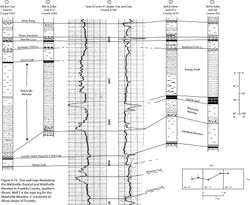

Moreover, no single well log fully characterizes the Walshville Member because the Walshville is both older than and laterally intergrading with the Herrin Coal. A suite of five logs thus has been prepared as a composite type section for the Walshville Member (Figure 4-73). Graphic logs of four coal-test borings and the electric log of one oil-test hole provide a profile 1.8 mi (2.9 km) long across the Walshville channel in Secs. 10, 11, and 12, T7S, R1E, Franklin County, Illinois. The four coal-test holes were cored and ISGS geologists logged the cores. The three eastern (right-hand) logs show thick Herrin Coal containing “splits” of clastic rock and overlying an upward-fining succession, the Walshville Member. In the two western logs, the Walshville Member is much thicker and fills a channel cut nearly to the Excello Shale. Overlying the Walshville Member in the two western logs is thin Herrin Coal at much higher elevation than found to the east. It is likely that the Herrin Coal on the western side of the channel consists of peat mats that were torn out and rafted away from their sites of accumulation.

Type author(s)

This report.

Type status

Logs of the Bell & Zoller coal-test holes are filed in the Coal Section of the ISGS. Logs of the oil-test hole are filed at the Geological Records Unit of the ISGS. No cores were saved from these borings.

Reference section

None.

Stratigraphic relationships

The existence of what is now called the Walshville channel was long known because of its impact on coal mining. Potter and Simon (1961) mapped the channel but incorrectly interpreted its filling as Anvil Rock Sandstone (Shelburn Formation), which is younger than the Herrin Coal. Johnson (1972) and Allgaier and Hopkins (1975) named the Walshville channel and correctly deduced that it formed partly contemporaneous with the Herrin peat.

As defined here, the Walshville Member is closely analogous to the Galatia Member. Incision of the Walshville channel began prior to Herrin peat development, probably while the Herrin underclay (paleosol) was forming elsewhere. The channel cuts at least as deeply as the Hanover Limestone and may cut deeper, although “stacking” with older valley-fill deposits has taken place (Palmer et al. 1979). Infilling (largely sand) began prior to the onset of peat formation, but the channel remained active throughout the time of peat development. As a result, Herrin Coal is absent along the channel axis, aside from occasional coal stringers that probably represent rafted peat. Along both margins of the Walshville channel, the coal is “split” with layers of shale and siltstone. Notably, the “blue band” in the lower part of the seam thickens from its usual 2 to 3 in. (5 to 8 cm) away from the channel to at least several feet (≥1 m) proximal to the channel. This relationship has been observed directly in underground mines.

When peat accumulation terminated, thick deposits of gray, nonmarine shale, siltstone, and sandstone overlay the Herrin Coal along the Walshville channel. These deposits are collectively termed Energy Shale Member. Although strata of the Walshville and Energy Members may intergrade, the sandstone that overlies the coal is considered part of the Energy.

So far as is known, no channel other than the Walshville remained active during Herrin peat formation. A few examples of shallow channel or valley-fill deposits older than the Herrin and younger than the Briar Hill Coal are known. These deposits are here considered part of the Walshville Member.

Extent and thickness

Numerous maps that depict the Walshville channel have been published. The most recent map, that of Treworgy et al. (2000), is essentially unchanged from Treworgy and Bargh (1984). As mapped, the channel (defined by the absence of Herrin Coal) extends across the basin from the northern outcrop in Douglas County to the southern outcrop in Jackson County, a distance of more than 200 mi (320 km). The width of the broadly looping feature varies from less than 1 to more than 3 mi (~1 to 5 km). Channel deposits attain a thickness of more than 215 ft (65 m; Figure 4-73).

Other channels filled with the Walshville Member are poorly documented. Examples have been seen on regional cross sections in southeastern Lawrence and north-central Wayne Counties. Filled mostly with sandstone, these channels truncate the Briar Hill Coal but not the Springfield. Potter (1963) mapped the thickness of sandstone between the Springfield and Herrin Coals in the southern part of the Illinois Basin, but this map combines the Walshville with the older Vermilionville Sandstone in some areas while ignoring the Walshville channel proper because this was believed to be filled with Anvil Rock Sandstone. A section from Willman and Payne (1942) illustrates probable Walshville Member in LaSalle County, northern Illinois. Willman and Payne called the sandstone Vermilionville, but the sandstone directly underlies the Herrin Coal (Figure 4-65).

Lithology

Although core data are plentiful, few details on the lithology of the Walshville Member have been assembled. Valley-fill deposits below the Herrin Coal level are largely sandstone that grades upward to siltstone, silty shale, and interlaminated shale and siltstone. Some sample and core logs indicate basal conglomerate that contains limestone, siderite, and shale clasts. Stringers of coal, probably rafted peat, are commonly present. The rock layers or “splits” in the Herrin Coal along the channel are largely gray, massive to weakly laminated siltstone and silty shale.

Core(s)

Photograph(s)

Contacts

The lower contact is erosional to units at least as old as the Hanover Limestone Member. Laterally, the upper part of the Walshville Member intertongues with the Herrin Coal. The upper contact seems to be gradational to the Energy Shale Member.

Well log characteristics

Wireline logs generally show an upward-fining profile. Limits of channels can be mapped by tracking the truncation of older members.

Fossils

Only transported plant remains and peat stringers have been documented.

Age and correlation

Based on the presence of Walshville Member sandstone beneath the Herrin Coal, the river that is represented by the Walshville channel was present prior to the onset of Herrin peat formation and continued to flow during and after peat formation in its latter stages as an estuary. Thus, the Walshville Member is contemporaneous in age with the Herrin Coal and its underclay, and with the Energy Shale Member, at least in part. Comparable channels outside the Illinois Basin have not been identified.

Environments of deposition

Like the Galatia Member, the Walshville Member fills paleovalleys that were cut during the eustatic lowstand that preceded peat accumulation. Early deposits, largely of sand, were probably laid down by meandering rivers. The Walshville channel apparently did not establish as wide a meander belt as the Galatia channel. Perhaps resistant layers, such as the St. David Limestone and the Springfield peat (coal), restricted lateral migration of the channel. Backfilling was largely complete by the time of maximum lowstand, when Herrin peat began to develop. Growing vegetation and fibrous peat deposits largely prevented lateral migration, locking meanders in place. Periodic floods carried clastic sediment into flanking peat swamps, creating “splits.” Rapid marine transgression drowned the peat deposit, converting the Walshville channel to an estuary in which gray mud and silt (Energy Shale) accumulated.

Economic importance

This unit has a large indirect impact on mining the Herrin Coal. Thick low-sulfur coal developed along channel margins, but coal did not develop along the channel axis.

Remarks

References

- Allgaier, G.J., and M.E. Hopkins, 1975, Reserves of the Herrin (No. 6) Coal in the Fairfield Basin in southeastern Illinois: Illinois State Geological Survey, Circular 489, 31 p., 2 pls.

- Callary, E., 2009, Place names of Illinois: Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 425 p.

- Dutcher, L.A., R.R. Dutcher, and M.E. Hopkins, 1977, Geology of southern Illinois coal deposits: Geological Society of America, North-Central Section Field Guide, v. 2, p. 2–33, published by Department of Geology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

- Dutcher, L.A., R.R. Dutcher, and J.E Utgaard, 1983, Geology of the No. 5 and No. 6 Coals of southern Illinois: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Field Guide for Eastern Section, p. 1–52, published by Department of Geology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

- Johnson, D.O., 1972, Stratigraphic analysis of the interval between the Herrin (No. 6) Coal and the Piasa Limestone in southwestern Illinois: Urbana, University of Illinois, Ph.D. thesis, 105 p.

- Ledvina, C.T., 1988, The mining geology of the Herrin (No. 6) and Springfield (No. 5) Coals in Illinois—Discrete features: Chicago, Northeastern Illinois University, M.S. thesis, 670 p.

- Palmer, J.E., R.J. Jacobson, and C.B. Trask, 1979, Depositional environments of strata of late Desmoinesian age overlying the Herrin (No. 6) Coal Member in southwestern Illinois, in J.E. Palmer and R.R. Dutcher, eds., Depositional and structural history of the Pennsylvanian System in the Illinois Basin, Part 2, Invited papers: Ninth International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology, Field Trip 9: Illinois State Geological Survey, Guidebook 15A, p. 92–102.

- Potter, P.E., 1963, Late Paleozoic sandstones of the Illinois Basin: Illinois State Geological Survey, Report of Investigations 217, 92 p., 1 pl.

- Potter, P.E., and J.A. Simon, 1961, Anvil Rock Sandstone and channel cutouts of Herrin (No. 6) Coal in west-central Illinois: Illinois State Geological Survey, Circular 314, 12 p., 2 pls.

- Treworgy, C.G., and M.H. Bargh, 1984, Coal resources of Illinois: Illinois State Geological Survey, 6 maps, 1:500,000.

- Treworgy, C.G., C.P. Korose, and C.L. Wiscombe, 2000, Availability of the Herrin Coal for mining in Illinois: Illinois State Geological Survey, Illinois Minerals 120, 54 p., 3 pls.

- Willman, H.B., and J.N. Payne, 1942, Geology and mineral resources of the Marseilles, Ottawa, and Streator Quadrangles: Illinois State Geological Survey, Bulletin 66, 388 p., 29 pls.

ISGS Codes

| Stratigraphic Code | Geo Unit Designation |

|---|---|